Benchmark Your Value-Added Preconstruction with Data

Join’s platform is used by teams across North America to manage preconstruction decision making. This includes information typically found in traditional value engineering logs, risk and opportunity logs, and design action logs and represents a broad cross-section of options explored for different types of projects in multiple locales.

Examining the data that teams have managed with Join, there are a few broad patterns that we want to share to help teams benchmark your own efforts and set expectations relative to the market: how cost impacts are distributed, where to focus your efforts when time is limited, and how many ideas you need to bring to the table.

What Data and Where Did it Come From?

Teams use Join to evaluate and track changes to a project’s design and budget relative to some baseline. These changes (or ‘items’ in Join) might be design or program changes, value-engineering decisions, or be the result of another driving factor such as a constructability review.

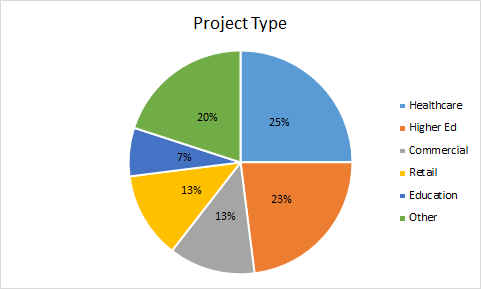

The results that we’re reporting here are aggregated across historical projects that teams managed with Join, which includes a wide range of new construction and renovation project types. This includes everything from wastewater plants to commercial offices and multifamily housing. Relative to the wider market, medical facilities and higher education are overrepresented in this sampling.

We wanted to examine whether there were patterns in the relative cost of items — e.g. how the cost of the item compared to the overall construction value of the project — that are considered during preconstruction. Because projects in Join come from a diverse population of project types and sizes, we first normalized the data to make it easier to examine trends.

All of the data below represents normalized item costs, calculated as the absolute value of the cost impact of an item divided by the baseline estimate. Scaling the cost impact relative to the project budget gives a sense for how “big” items are in dollar terms. Using the absolute value allows for an apples-to-apples comparison regardless of whether an item increases or decreases the project estimate.

Looking through the data, we’ve found three things:

- There are a lot of nickels to pick up: most projects evaluate several dozen changes, and most items are small

- Most of the cost impact is concentrated in the largest 25% of items: when short on time, focus on the big tickets.

- You can approximate the number of items you need to have on the table based on the total budget impact that you are seeking

Most Items have a Small Cost Impact

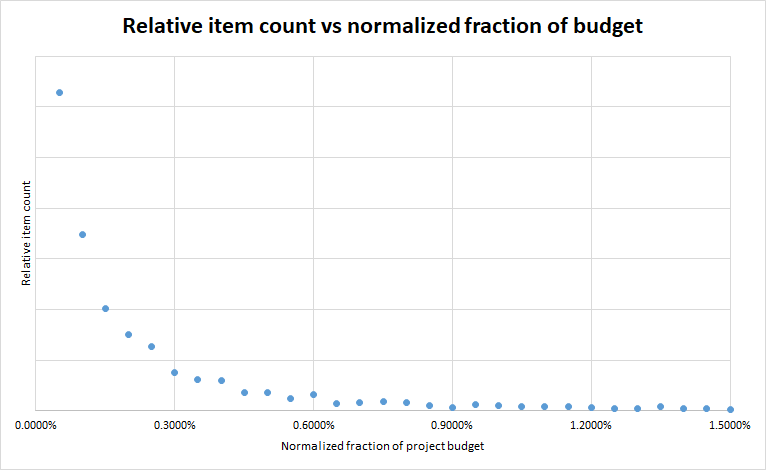

This graph summarizes the relative number of items with different normalized cost impacts. For every item that changes 1.0-1.5% of a project’s budget, there are typically 3 to 4 items that change the budget by 0.1-0.15%, and 6 to 7 that change it by 0.05-0.1%. Using a $50m project as an example, this means there are many more $50k risks and opportunities than there are $500k ones.

This graph backs what some teams already knew after spending days working through many decisions only to find that they had saved a few scant dollars per square foot: most changes have a small impact.

One conclusion: There are a lot of opportunities in most projects, and uncovering them requires a diverse set of experienced eyes. If the team has fewer than 50-100 items on the table at any one time, you’re probably leaving opportunity on the table.

Item Cost Impacts Have a “Fat Tail”

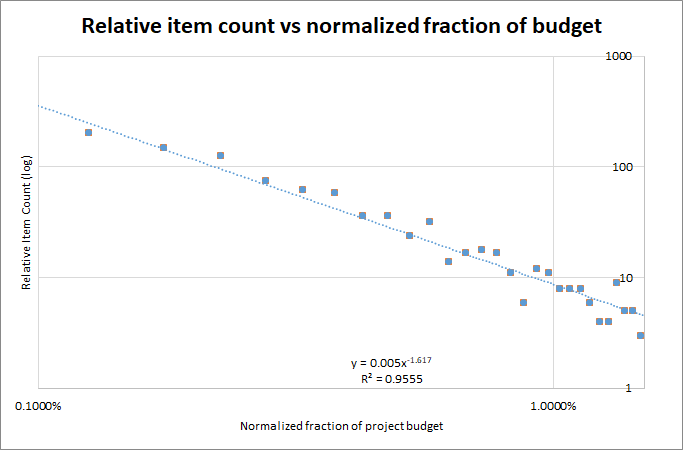

If you’re pressed for time, focus on the biggest items. While most items are small, the distribution of items has an important property: it has a “fat tail”. We can see this replotting our relative item counts on logarithmic axes. This shows a straight line, statistically resembling a power law distribution.

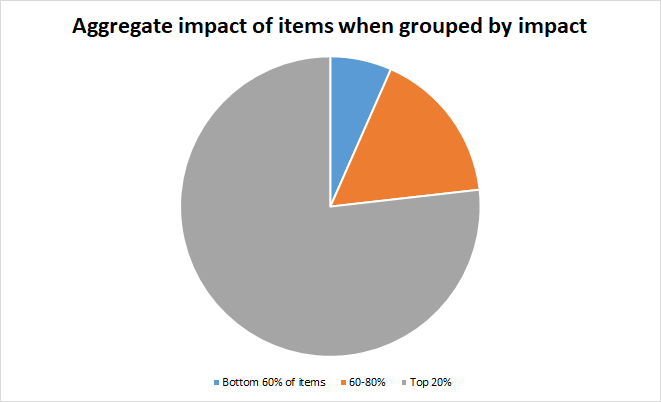

What this means is that while most items are small, the cost impact is disproportionately concentrated in the largest items and that preconstruction decisions follow the Pareto Principle, aka the “80/20 rule” — that generally, 20% of causes are responsible for 80% of effects. Our data shows that over 75% of the potential cost impact is in the largest 20% of items.

The takeaway: if you are pressed for time and concerned about budget, focus on the biggest changes.

How Many Items Do You Need?

The median item with a cost impact is about 0.1% of the budget. Throwing away outliers, we find that the mean cost impact is around 0.24%. We can use these items to ballpark how many items need to be on the table if your team is seeking a particular target to change the budget. From the data in Join, we find that the fraction of proposed changes that ultimately get accepted varies widely across projects — some teams will take everything on the table while others end up rejecting the majority of ideas; middle of the road projects accept around 1 in 3 proposed items. Looking at how the number of items needed varies with this acceptance rate, we get the chart below.

Here’s how to use the chart:

- Determine the total budget impact you’re seeking, whether its targeting cost savings or additional budget to allocate, and locate the corresponding row.

- Find the column that approximates the fraction of proposed ideas that you think will be accepted by the team. 1 in 3 is common, but the past experience of your team is the best guide.

- Look up the approximate number of items that need to be proposed to achieve the stated goal. Now get to work!

| Fraction of proposed items that are accepted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Budget Impact |

1 in 10 | 1 in 5 | 1 in 3 | 1 in 2 | All |

| 1% | 49 | 24 | 15 | 10 | 5 |

| 5% | 245 | 122 | 73 | 49 | 24 |

| 10% | 489 | 245 | 147 | 98 | 49 |

| 20% | 979 | 489 | 294 | 196 | 98 |

These are ballpark numbers, and teams’ experiences may vary: for example, early in a project, large-scale programmatic changes lead to dramatic cost changes. But even as an approximation, these numbers can drive valuable conversations at the outset of a decision-making cycle. Especially for teams facing significant budget misses, spending even a little time to get a better sense of what’s needed can tremendously help to put you on a path to success — whether that’s managing your team’s expectations or shifting your original approach to brainstorm design and scope changes. Then, you can either prepare to do enough work to get a significant number of opportunities on the table or prepare the rest of the team for a potentially painful process of accepting a large fraction of the ideas that are available.

Conclusions

Looking at historical data in Join, we found three things: most ideas have a small cost impact, the largest impact items are where to focus when time is short, and based on a target budget impact, we can approximate the number of ideas that need to be on the table.

We know that project teams face two challenges in executing on these conclusions:

- Managing and executing complex decisions in a timely manner

- Having a consistent view across multiple projects that allows your team to assess progress and leverage work that has happened in previous efforts on new work.

If you’re interested in how Join may be able to help solve either of these challenges, give us a shout.